On Shrove Tuesday night, February 28th, 1995, I fetched up at Dublin’s R.D.S. and, as I wound my way up the long avenue, in past the security hut and around the clusters of other invitees and liggers, my mind was cast back twelve months, back to a time when we were all a bit less sure on our feet. A handful of us had gathered to support our friend and colleague, Dónal Dineen: ‘No Disco’, the programme he reluctantly presented and the one that I enthusiastically but naively devised and produced was about to claim the Vincent Hanley Memorial Award at the Hot Press Music Critics’ Awards. Much to our surprise, we received one of the best receptions of the night, but then ‘surprise’ is a dominant theme throughout the early history of ‘No Disco’.

Among the other winners that Pancake Night were A House, who took the gongs for ‘Best Single’ and ‘Best Video’ for ‘Endless Art’ and Terri Hooley, the Belfast maverick who, among other things, founded the Good Vibrations record shop and cajoled The Undertones through their labour. We were in good company and had come a long way in the fifteen months since ‘No Disco’ first stumbled onto the national airwaves at the end of September, 1993.

The Hot Press event was sponsored by one of the drinks companies, Smithwicks I think, and a few of us stayed around well into the night, Dónal apart. He doesn’t drink and, as long as I know him, has always been in a rush to beat a hasty retreat. It was a strange old night as I recall it but an important one for the series on several levels. I’d been based in Dublin for the previous number of months, attending a full-time training course out in RTÉ and, for practical reasons, just couldn’t keep going. I was reluctantly cutting my lingering ties with ‘No Disco’ and, by killing my darling, was doing the show a real favour.

‘No Disco’ was first broadcast on Thursday night, September 30th, 1993, and ran for the guts of a decade. The decision by RTÉ to discontinue the programme certainly created far more of a stir than the decision to start it all in the first place and its fair to say that the series was held deliberately under the radar, regarded largely as more of a strategic and technical experiment than an editorial one. Far from being launched, the series just fell into the schedules, like a flutered old lag around the fringes of a hen night. Brian Boyd, writing in The Irish Times on the week before we aired the first episode, opened his preview as follows: ‘Oh dear, they’re at it again. RTÉ are putting on a new young person’s music programme – pass the remote control and make it quick’. And it was difficult to blame his cynicism, especially given how even some of our own colleagues, baffled by what we were trying to do, expected ‘No Disco’ to fail so miserably too.

Twenty-two years after we started work on the very first episode, I’m still routinely reminded of ‘No Disco’. To a generation of middle-aged, music-loving parents now dealing with their own surly teenage sons and daughters, I’ll forever be part of the reason they were so distracted way back, late on Thursday nights, on what was then Network 2. At various work and social events, weddings and funerals over the years, I’ve been subjected to all manner of loose conversation regarding Paul Weller, Tindersticks, Kristin Hersh, The Afghan Whigs and the many other flag- bearers who dominated the early ‘No Disco’ songbook. ‘Ah, ‘’twas a long time ago’, I say, flattered. ‘There’s been a lot of water under the bridge since’. And then I suck the remaining air out of whatever room I’m in. I never learn.

‘No Disco’ has always attracted an awful lot of old guff, and I’ve been responsible for much of it myself. What’s undeniable is that, once this quite bizarre series settled down, it became an appointment to view – or, to our sizeable student cohort, to record on VHS – for a loyal and perfectly deformed audience of anoraks, enthusiasts, freaks and those who had issues dealing with regular society. It was a public health service as much as it was a public service statement.

In hindsight, it was Philip Kampff, then an RTÉ television producer who,among other things, masterminded the Gerry Ryan/Lambo heist as part of Gay Byrne’s radio series and later devised The Lyrics Board, planted the first seeds. During the late 1980s, Philip had exploited the production facilities in RTÉ’s regional studios to help feed a monster children’s television series called ‘Scratch Saturday’. I’d been recruited as a free-lancer onto his programme staff, producing a weekly music slot from RTÉ Cork’s new, city centre base in Father Mathew Street. When, four years later – and after an exotic trip around the fringes of the music industry in London and beyond – I returned to my old desk in Cork and informed the small band of local technicians that we’d shortly be producing an hour of music television every week for national broadcast, I was laughed all the way back out to Blackpool.

‘No Disco’ formed the first part of a broader RTÉ commitment to what was then referred to as ‘regional broadcasting’. The production base in Cork has since expanded beyond all recognition and is a far cry from the empty shell in which we set up shop in August, 1993, both in terms of the quality and quantity of it’s output. And so the next time you see John Creedon take a retro vehicle on a scenic driving tour of Ireland, you can blame Dónal Dineen.

I was working with Jeff Brennan in The Rock Garden in Temple Bar in Dublin during the Summer of 1993 when I was summoned out to RTÉ to meet Eugene Murray. Eugene had been a former editor on Today Tonight and, now running RTÉ’s Presentation Division, believed we could produce cost-effective programming [or, if you prefer, no-budget television] from the skeleton facility in Cork, using the old ‘Scratch Saturday’ template and building on it. Having few other interests, commitments or concerns, I defaulted to what I knew best and, taking my cues variously from previous RTÉ music programmes like ‘MT USA’ and Dave Heffernan’s inserts into ‘Anything Goes’, I put together the most simple formula I could. Ten weeks later we were on air.

On the night of ‘No Disco’’s first transmission, a small group of us met up in Cork to mark what was possibly the closest the county had come to a modern miracle since the statues moved down in Ballinspittle. It was an enormous achievement to actually get the thing on air, all the more so given that neither Dónal or myself had the first idea what we were doing. Cockiness and mindless enthusiasm were always only going to get us so far and, while we were teething, we were often shovelled onto air by a support cast of notables who, I am sure, found the whole set-up quite erratic. I’ve thanked the likes of Tom McSweeney, Olan O’Brien, Antóin O’Callaghan, Tom Bannon and Déirdre O’Grady in the past and I’m doing it again here now: they rarely, if ever, feature in the ‘No Disco’ story. And yet in many respects, they are the first chapters of the ‘No Disco’ story.

Between one thing and another, it was Marty Morrissey, now a well- known Gaelic Games broadcaster but then one of a number of young reporters billeted in RTÉ Radio Cork on Union Quay, who convinced Jurys Hotel on Western Road to allow us watch our debut programme go out on air from a vacant suite on their complex. The first video on the first programme was ‘Cannonball’ by The Breeders, but by the time we got to the ten minute Dead Can Dance segment, we’d lost the room. Marty barely made it past the opening sequence and, more an M.O.R. man than an A.R. Kane man, wasn’t entirely sure what he was seeing. We didn’t use credits at the end of the programme and, as the first hour wound down and we faded out into the closing RTÉ Cork logo, my friends and colleagues applauded politely and kindly. It was as if we’d been gathered in a courtroom and I’d just been acquitted of murder but found guilty of manslaughter. I wanted the mini-bar to open up and swallow me whole.

The really great things about ‘No Disco’ ultimately un-did it. Based outside of Dublin gave us a freedom and a licence to roam, more or less, as we wanted. We weren’t privvy to the carry-on in Montrose and I fancifully saw myself as a latter-day Wolfe Tone, a colonial outsider railing against the machine. Even though, on one level, my work was defined largely by that same machine.

I used to wonder what would have happened had senior RTÉ managers at the time had their way with ‘No Disco’ ? If, for instance, they had daily physical access to us ? Because after only four weeks on air, ‘No Disco’ was an issue: word filtered back to me that Dónal was a real concern, that the music policy was considered far too extreme and that ‘No Disco’ wasn’t really a broadcastable programme at all. But we held our ground – because, I guess, we could – put our heads down and just pedalled harder. I may not have always known what I was doing but I certainly knew what I wanted to do. And then The Irish Times came to the party.

Brian Boyd contributed a weekly column called ‘Hot Licks’ to the paper’s Friday morning arts and music coverage and, from very early on, was down enthusiastically with the series. Word seemed to be spreading, however slowly and, in the days before e-mail, we’d even received a trickle of correspondence from viewers by post. On one occasion the telephone in the office actually rang and a ‘fan’ was on the other end. We had other friends out there too, of course: Dónal Scannell was a fellow traveller and a loyal snout inside the belly of the beast in RTÉ while Áine Healy played a starring role as our administrative back-up in Dublin. Apart from Brian Boyd, we had other agents in the music pages too, all of whom sung our praises often and loudly. And it all helped. What ‘No Disco’ lacked in terms of audience numbers and branding support, it made up for with that rarest of commodities: real credibility among a small cohort who could see beyond the obvious.

And Dónal Dineen takes the credit here. I first encountered him through Dónal Scannell, back when we were publishing a free, monthly music paper in Dublin called DropOut. We shared a Southern sensibility and a keen interest in the GAA: we once spent seven consecutive nights crawling a range of Dublin’s flesh-pots for a feature called ‘It’s a Shame about Cabaret’ and were lucky to survive up in The Four Provinces in Ranelagh when we were turned on by a couple of young bucks from up the country somewhere.

Dónal was in the autumn of his club football career with his beloved Rathmore – he is a contemporary and clubmate of the former Kerry senior goalkeeper, Declan O’Keeffe – and our small production office would often resound with tales from the darker side of the dressing room. Years before Croke Park was re-developed and well before the advent of media boycotts, multiple sponsors, dieticians, head doctors and team flunkeys, Gaelic Games were hugely derided by some of the louder elements of the Dublin media set. Fine writers like Gerry McGovern were routinely dismissed because, with their ‘bog-ball’ and ‘stick-fighting’, they dared to be proud of what made them and maybe brought different values to the editorial tables. Dónal would have gladly swapped any number of Hot Press awards for an O’Donoghue Cup medal with Rathmore and that pursuit, for a time, was every bit as intense as they man himself and his long-running affair with sound.

It was during the course of a DropOut production weekend in a semi- detached house in Knocklyon that we first heard [and he became obsessed with] David Gray’s first album, ‘A Century Ends’, which had been submitted for review by one of the record companies. That was how humble the beginnings of that relationship were and it’s probably fair to say that the growth in David Gray’s popularity in Ireland owed, to a large degree, to the exposure he received on ‘No Disco’, where he was a mainstay. Over the course of the first eighteen months of the series, both David Gray and ‘No Disco’ found their feet, voice and audiences in tandem. And when Dónal Scannell brought Gray to Cork and Dublin for his first nervous live shows here, ‘No Disco’ was the primary driver for that.

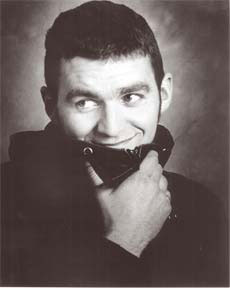

It certainly wasn’t intentional and I didn’t really appreciate it at the time but, looking back now, the tone of the series – dislocated, informed, intense, regional, soft and considerate – was based entirely around Dónal’s personality. He’s by far the most reluctant and easily the most interesting ‘presenter’ I’ve worked with, most probably because he isn’t and never was a presenter in the first place. One of the many things that set him apart, and what disconcerted many of the ‘industry professionals’ who encountered him, was that he saw right through the medium and was absolutely discommoded by it. He never saw ‘No Disco’ as a stepping stone to a career in light entertainment but more of a stepping stone back into obscurity. He was everything he said he was and he had no side: he did what he did in the interests of quality music and, to that end, was always more emotionally comfortable and secure on radio, which was his real passion. And so I wasn’t overly surprised to see him unveiled alongside Eamonn Dunphy, Anne-Marie Hourihane and others as part of the first Radio Ireland line-up in 1997, where his late-night ‘Here Comes The Night’ programme was, for a number of years, an essential listen. My only surprise was that he managed to hang around there for so long.

Because there, as on ‘No Disco’, he really did give it all for the music he believed in, and maybe far too much sometimes. We’d routinely argue over set-lists for the show: he brought the sophistication, the breath of reference and the smarts and I brought the noise and the pale indie shapes. His scripts would often sparkle: Dónal’s writing owed more to Con Houlihan than to Nick Kent and he’d agonise and pore over every line. One of his best print pieces was actually about Gaelic football, a gorgeous personal essay he did about Rathmore for the Munster Football Final programme in July, 1995. ‘The special sense of community that arises from the sharing of dreams is a precious part of the life of place’, he wrote. It could have doubled as one of his softly-voiced introductions to a new Stina Nordenstam release or a lost Red House Painters track.

Some of our production priorities were far less romantic, though. Our cameramen and sound recordists were, at least during the early years, actually scheduled onto the RTE News service in Cork and, as happened once or twice, we’d have to abandon or suspend a planned shoot in the event of a news story breaking. It was all very laissez-faire but Joe and Tony McCarthy, Tony Cournane, Paul O’Flynn and Brian O’Mahony gave us sterling service over the years, as did Dónal and Jim Wylde, whenever they were sprung from the Waterford bureau and pressed into service, dispatched to take care of ‘the mad shit in Cork’.

But it was a slow process and, throughout those early months, we were viewed with a combination of bafflement and suspicion, more to do with what we were trying to do than for who we were, I suspect. But once ‘No Disco’ settled, and once the first positive notices started to filter through, a real gang mentality grew up around the series and everyone felt far more secure in the boat. For those who sailed in her, it was a scenic and exotic passage in steerage class, even if it often felt like we were travelling without a compass.

We recorded Dónal’s pieces to camera on the top floor of the RTÉ Cork building every Monday night, working around the demands of the newsroom. Our location was a cold, breeze-blocked space that we’d often supplement with whatever odd props we could pinch from the children’s TV stash down-stairs. I spent ages one afternoon cutting the letters that comprised the words ‘No Disco’ from a load of old Styrofoam wrapping that had come with some piece of technical kit installed in another part of the building. We got ferocious mileage from those self- standing pieces but my hands were welted for weeks afterwards.

But the more established we became, the more confident we grew and we soon reached a point where we didn’t have to explain or introduce ourselves to bands, handlers or publicists, which was another huge leap forwards. Paul Weller, then in the early stages of an unexpected career revival after years in the sidings, requested a date with us and I remember heading out nervously one Sunday evening to interview him after he’d finished a sound-check in The City Hall. He could be a spiky character at the best of times but I was assured that he liked the cut of the programme and had watched a couple of episodes: so much so that he sang like a canary and was happy to keep going way beyond the allotted half-hour. It was his father, who was also his manager, who arrived into the posh seats and wrapped us up so they could actually open the main doors and start getting folk into the hall.

By the start of the second series, the programme scored a rare audience with Lou Reed in Paris, which we gratefully accepted and during which Dónal and his interviewee developed a serious rapport, touching on art, design and photography as they ate, in real detail, into various aspects of Reed’s career. It is highly unlikely that, on that entire promotional campaign in support of ‘Set The Twilight Reeling’, Reed encountered anything as far- ranging and informed as the hour he spent with our boy. But by then we’d already done the likes of Suede, St. Etienne, David Gray, Pavement, Kristin Hersh and, most memorably, David Gedge from The Wedding Present, who took the short walk across from Sir Henry’s to talk to us in Father Mathew Street. And we’d picked up a few pointers – and no few brownie points – along the way.

As well as knocking off interviews with anyone of note – and many of no note whatsoever – who came our way, we also began to dabble with live, stripped back ‘sessions’, initially with a number of largely Dublin- based acts who’d travel to Cork for the day and endure us as we’d shoot multiple takes for editing later. Edwyn Collins did a gorgeous two- song set for us upstairs in The Old Oak one afternoon, performing ‘Low Expectations’ and ‘Gorgeous George’ from his comeback Setanta album, while we also recorded in The Triskel with Martin Stephenson, The Firkin Crane with The Divine Comedy and The CAT Club with The Revenants. Dónal had already introduced me to the Kerry singer-songwriter, John Hegarty, and we did a terrific session with him, also in The Triskel, that yielded a golden version of ‘Bonfire Night’, a beautiful song we both adored and which sat perfectly with our own personal sensibilities. I’ve covered this aspect of the series in a previous post about The Divine Comedy, available here.

We wrapped up ‘No Disco’’s first season with a live benefit concert, in support of the Cork Aids Alliance, up in Nancy Spain’s on Barrack Street on May 17th, 1994. A local PR company run by Jean Kearney and Maura O’Keeffe had come to me with the suggestion, adamant that the ‘No Disco’ name was enough to carry a show like this, and wanted to guage our interest. I never once thought that we’d ram Nancy’s on a Sunday night with a bill that comprised, basically, of our friends – Engine Alley, Blink, Sack, LMNO Pelican and Treehouse – all of whom put themselves out on our behalf and never requested a single bean. Jim Carroll spun discs long into the night, Dónal did a short set, said a few words from the stage and was basically molested when he wandered through the venue. It was into the small hours when we cleared the hall, pulled down the P.A. and got the visiting bands back safely on the road and, as I made the short journey down-hill, home to my flat on Sullivan’s Quay, I wondered if ‘No Disco’ would be returning for a second series ?

I needn’t have worried. Not only had ‘No Disco’ found and developed an audience, the reviews and the general critical reaction gave us a bit more leeway in our discussions with RTÉ. We’d gotten onto air, stayed there and, by so doing, won friends in unlikely places. So by the time I checked out of the series for good, ‘No Disco’ was on it’s way. But it was Rory Cobbe and Dónal who developed the breath and the scope of the series beyond all recognition, putting flesh on what was still a very crudely formed skeleton. The programme became far broader in tone and in content, and I suspect that Rory enabled Dónal in ways which I never could have done and, by the third series, ‘No Disco’ had really found it’s meter.

I’ve seen Dónal a handful of times in the twenty years since we soldiered so intensely and intently together in Cork. We last spoke when I talked him into doing the voice-over on Ross Whitaker’s beautiful documentary film, ‘When Ali Came To Ireland’, and I was thrilled skinny when he agreed to be involved. Moreso again when I saw the final cut and heard that voice back on screen one more time. I’m not sure when we’ll meet again – given our recent record it’s unlikely to be any time soon – but, when eventually we do, we’ll talk about Gaelic football, enquire after our respective families and recall an old in-joke about Paul Weller headbands.

And then one of us will mention ‘Asleep In The Back’ by Elbow or ‘The Idiots’ by Republic of Loose or ‘Your Ghost’ by Kristin Hersh and we’ll lose ourselves for a moment because, as much as some things change, other things never change at all.

I’d like to complain about the video quality of those 2 youtube videos – oh wait we dug those out 🙂 Would seriously love to see some more of those sessions you recorded – The Revenants one is my new holy grail. Also John Hegarty and that Lou Reed interview sounds amazing. When are RTE going to do a show for us fortysomethings, digging out these old sessions and interviews, kinda like a Fanning sessions archive for TV..

LikeLike

you did indeed… I agree, it would be great if RTE could do a show along the lines of Fanning Sessions – there is so much gold in them archives… and did you have any luck in tracing down those VHS tapes promised to you on your blog?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely. We could call it The Antiques Roadshow. Colm

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent article. You’ve made me very nostalgic for that exciting time when each week some new and quality music would appear on my radar. I used to record the show in it’s entirety, and watch it throughout the week until the following Thursday. I was still watching those tapes regularly a decade later, I still have a few, but they’ve been in storage for the last while, and I’m unsure how many would even play now. Several of the tapes were left in an ex’s house, and I mourned them more than the relationship. I’m not entirely sure what I still have, but some quiet weekend I’ll rummage through them all, and take to Youtube. That Lou Reed interview was a definite highlight, it was memorable for the quality of it, but also I remember it being around the same time Dave Fanning spoke to him, and Lou didn’t take to poor Dave in the same way as Donal at all!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ray you got a good setup for ripping VHS? Might be able to drum up a few tapes..

LikeLike

Cool! It’s ok, just an adaptor set up to a pc, but it’s effective. The VHS player is a six head one, so if the tape is in good condition, the quality is usually pretty good,It’s currently in storage, but I’m been meaning to get it out again to play with it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just keep it legal now lads …

LikeLiked by 3 people

‘No Disco’ youtube playlist featuring sessions and interviews and the odd video https://youtu.be/-PpT-hruuMA?list=PLNs2VCbSBS_pPzdHOlRI0qkSnh27CLC_Q

LikeLiked by 1 person

I must agree with Fanning Sessions, I would love to see some classic ND moments!

LikeLike

Robert Poss from Band Of Susans, here. I have a VHS tape of my appearance on No Disco. I’ve just sent it off to get transferred. I recall being very nervous, since as used as I was to print and radio interviews, being on camera terrified me slightly. Cheers.

LikeLike

Thanks very much for taking the time to read and to post, Robert. Being terrified on camera is a recurring theme in the No Disco story. Hope you’re keeping well and healthy. All the best, Colm.

LikeLike

Fondly remembered and fondly read. Donal Dineen lived across the road from us on Sullivan Street off the North Circular years ago and regretfully we only ever shared a few nodded hellos. My fault entirely. It really was a special programme that made some disparate souls feel connected in their (no)disconnectedness. Long live the Sentinel!

LikeLike

Thanks Enda. Donal is a life-long Northsider. The programme certainly served a public purpose and is rightly remember fondly, if maybe over-fondly at times ? All the best, Colm.

LikeLiked by 1 person