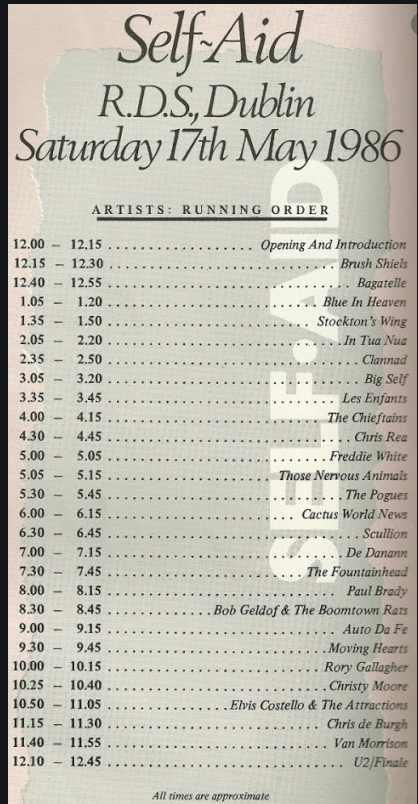

The ‘Self Aid’ live concert that took place in Dublin’s Royal Dublin Society showgrounds on May 17, 1986, is unprecedented in the history of popular entertainment in Ireland. Never has such a high-profile, high-end indigenous line-up been assembled on the same bill: ‘Self Aid’ was headlined by U2 and also featured short live sets by Rory Gallagher, Van Morrison and The Boomtown Rats among numerous others. But rarely has the build-up to any concert been the subject of such sustained ideological debate and seldom has the fall-out from any show reverberated so loudly for so long afterwards.

‘Self Aid’ was a fourteen-hour, live music event broadcast over the course of an entire day, designed to raise funds for a job creation initiative and, through commitment from employers, to create jobs. The core conceit was laudable enough: during the mid-1980s, unemployment levels in Ireland were running at nearly 20% of the available workforce and emigration was rife. The country was in recession and listing badly: a well-known social justice campaigner, Sister Stanislaus Kennedy, claimed that during this period, one million people here were living in poverty.

We felt this as keenly as any on the northside of Cork. As Michael Moynihan writes in his book, Crisis and Comeback, by the mid-1980s, ‘Cork city had become a rust-belt region’, after three major local employers, Ford, Dunlop and Verolme Dockyard, all closed within eighteen months of each other. Following a second major fire at the city’s historic English Market, Cork Corporation toyed with the idea of turning the site into a car park. Is there a more appropriate metaphor for the story of Ireland during this decade ?

On July 13th, 1985, after we’d completed our Leaving Cert exams and left secondary school for good, an extraordinary live music event took place at Wembley Stadium in London and at the JFK Stadium in Philadelphia. Conceived by Bob Geldof, the Boomtown Rats’ singer, and organised by him and the prominent British promoter, Harvey Goldsmith, ‘Live Aid’ pulled the biggest names in popular music together for a spectacular, once-off global event to raise money to help famine relief in Ethiopia. It eventually generated well in excess of £100m and catapulted Geldof back into the public eye. The Dubliner has since become a powerful campaigner for global justice and his humanitarian work and advocacy in respect of emerging societies and the Third World dominates his legacy.

By any standards, ‘Live Aid’ is one of the most profoundly affecting live concerts in the history of modern entertainment: apart entirely from the money and the awareness it generated, it was yet another example of the compelling power of popular music. ‘Live Aid’ was a popular cultural device on which to hook a complicated conversation, but some of those live performances in London and Philadelphia – Queen, U2, Bowie, Paul McCartney – will never be forgotten. Bob Geldof recalls it at length in his 1986 autobiography, ‘Is That It?’ Indeed, were it not for ‘Live Aid’, it’s unlikely there would have been a Geldof autobiography at that point at all. As a musician he’d run out of gas but now, barely a year after I saw him front The Rats at a far-from-full Cork City Hall on the ‘In the Long Grass’ tour, he was one of the most recognisable figures on the planet.

Ireland’s national broadcaster, RTÉ, was one of the first European outlets to enthusiastically come on board with ‘Live Aid’. In ‘Is That It?’ Geldof claims that ‘without doubt, the Irish [Live Aid] Telethon was the best produced, resulting in the greatest net contribution per head of population’. This was all the more remarkable given the extent of social inequality on the country’s doorstep.

In the wake of the success of ‘Live Aid’, a number of similar events based on the same premise took place around the world. ‘Farm Aid’, pitched as an idea by Bob Dylan and originally organised by John Mellencamp, Willie Nelson and Neil Young, still endures, and with the same basic purpose: to raise funds for struggling American farmers. ‘Sport Aid’ was an obvious adjunct and was briefly popular, while the ‘telethon’ format – where money is pledged to various causes during live television strands – became, and remains, a popular conceit.

RTÉ’s ‘Live Aid’ coverage was led by Tony Boland, a senior producer at the broadcaster’s entertainment division who’d served his time on The Late Late Show and who was a long-time acquaintance of Geldof’s. When, a year later, himself and another formidable RTÉ programme-maker, Niall Mathews, suggested to RTÉ that an Irish television equivalent could focus on the extent of national unemployment, Geldof was one of his first calls.

Money raised by ‘Self Aid’ was administered by a board of trustees –working with some of the formal state agencies – on which sat the then RTÉ Director General, Vincent Finn, U2’s manager, Paul McGuinness, Justice Mella Carroll, trade unionist Peter Cassells, the aforementioned Sister Stanislaus Kennedy and others. Viewers were encouraged to donate money and employers were asked to pledge jobs on the day of the show, which was anchored from the RTÉ studios in Donnybrook and into which were fed a series of inserted links from around the country, as well as live coverage of the music in the RDS. The concert was promoted and run by Jim Aiken and the 30,000 tickets allocated to it, priced at £15, quickly sold out.

Geldof’s participation was clearly a key to unlocking the rest of the ‘Self-Aid’ line-up which, as well as the high-profile names, also featured the best of established local outfits, from Moving Hearts and De Danann to Paul Brady, Scullion and In Tua Nua who lined-up alongside a couple of British artists who, at the time, were regular visitors to Ireland and enjoyed special status here: Elvis Costello and [at the suggestion of Niall Matthews’ brother], Chris Rea. Such were Tony Boland’s powers of persuasion that, over sandwiches and soup at Adam Clayton’s house in Rathfarnham, U2 agreed to defer a planned Dublin show and made ‘Self Aid’ the band’s only European appearance of 1986.

‘Self Aid’ even had its own anthem. A single, ‘Let’s Make It Work’, written and performed by Paul Doran, then pitched as ‘an unemployed songwriter’, and Christy Moore, was released in advance of the event. With its distinctive lyrics – ‘I can dig a hole, I can climb a pole, I can work in a factory, I can assemble a TV’ – it remains a curio in the recent history of Irish music. Produced by Moore and Donal Lunny, and featuring a gold-plated backing band including the late Liam Óg Ó Floinn, Paul Brady and Larry Mullen, the song was unveiled on The Late Late Show the week before ‘Self Aid’. ‘Let’s Make It Work’ was afforded a special dispensation by the late disc jockey, Larry Gogan, who deemed it an honorary Number One single in Ireland, although it was far from the biggest-selling seven-incher in the country that week.

On his website, Paul Doran’s biography refers to ‘Self Aid’ as ‘a controversial event in Ireland, and one he came to regret his involvement in’. In the years since, his songs have been covered by Christy Moore, Mary Coughlan, Paulo Nutini and others and, two years ago, he released his first elpee.

‘Self Aid’ was more of an event that attracted legitimate critical discourse than a ‘controversial event’. It provoked debate from the get-go and, in the weeks leading up to the live concert, came under sustained scrutiny from a small but vocal cohort of the Irish media. The gut of that argument was captured in a spread of pieces in ‘In Dublin’ magazine – up until then a largely unremarkable listings magazine, based on the ‘Time Out’ model and edited by John Waters – which hit the capital’s news-stands days before ‘Self Aid’. Under the umbrella headline, ‘The Great Self Aid Farce’, the magazine ran a series of strongly-worded opinion pieces, led by the Derry-born writer and broadcaster, Eamonn McCann, that took issue with the event on a number of levels.

In his book, The Frontman: Bono [In the Name of Power], Harry Browne refers to this as a ‘groundswell of opinion on much of the Irish left’ that pointed to Self Aid’s ‘emphasis on positivity and the ‘pull up by our bootstraps’ type of capitalism of much of its rhetoric’. A suggestion was that this might do ‘more harm than the little good it would achieve through fund-raising for jobs-creation projects’.

Eamonn McCann was working, at the time, on an RTÉ television media series, ‘Slants’, and he put these points to ‘Self Aid’’s promoter, Jim Aiken, at a press conference in Dublin on May 1st, 1986, to launch the event. As the briefing came to an end, Aiken, an imposing, Armagh-born music industry veteran, suggested that McCann accompany him, rather, to an impromptu, two-person protest at the Russian Embassy to protest about the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl. What is accepted as the worst nuclear accident in history took place at a defective reactor in what is now northern Ukraine the previous week. According to a report on the launch in The Irish Independent, ‘McCann politely refused’ the invite.

Christy Moore, then as now one of the more politically involved musicians in the country and himself a long-time anti-nuclear campaigner, saw ‘Self Aid’ differently: ‘What harm can it do ?’, he asked The Irish Press newspaper. ‘There are many valid political reasons that can be found to criticise it, but it could have more positive value than the endless discoursing of politicians about the problem of unemployment’.

Bob Geldof was more forthright. ‘I know the arguments against ‘Self Aid’ and I rejected them when I was 14’, he told the media corps gathered backstage at the RDS on the day of the show. Geldof had made a late dash to Dublin from Cardiff, where he’d opened a rugby tournament for the ‘Sport Aid’ fund. Ireland, he claimed, was a country with ‘a Third World economy’ and he rejected the suggestion that, in respect of job creation, ‘Self Aid’ was doing the work of government. ‘If you say that, then you are abdicating your personal responsibility to the people around you’.

Tony Boland came out swinging in The Sunday Independent. ‘I can respect the fact that other people have objected on ideological grounds’, he told Willie Kealy. ‘But we live in a capitalist system, and we have to talk about jobs this side of the revolution, not after it’. ‘If nothing else’, Christy Moore added, ‘the show might lift people’s spirits for a day’. Which, I suspect, was a view shared by most of those who attended ‘Self Aid’ in person or who watched the event unfold live on television.

To many of us, ‘Self Aid’ was a day-out and a day-off, something different to do. A scarcely believable line-up to get worked up about and a reminder too that many of us were being reared for export. The noise around the event, justifiable as much of it may have been, was lost on the multitude.

And besides, I had far more pressing issues on my plate. About to turn eighteen, I’d started my first-year college exams and, in a distinctive twist on an old Irish parable, my mother was pregnant and my parents were the talk of the parish. My brother was born a number of weeks later and was named after the lead singer from Cactus World News, who played a storming teatime set at ‘Self Aid’. That says a lot about the house I grew up in.

Forswearing my books and notes, I spent May 17th, 1986, docked in front of the television, mainlining ‘Self Aid’. The highlights came early and often, as if the producers had cannily scheduled them to detonate at key intervals over the fourteen hours. Blue in Heaven’s ‘Red Dress’, a brooding, Doors-ish cut over a simple keyboard run and with no chorus, exploded during lunchtime. A high-camp, cinematic performance of ‘Slipaway’ by Les Enfants during the mid-afternoon. A fine, meaty set by The Fountainhead, the augmented Dublin two-piece who were about to release a cracking debut album, ‘The Burning Touch’, set the post-teatime pace, and it just kept coming. Just before 9, at the conclusion of his band’s short set, Bob Geldof announced on stage that The Boomtown Rats had just played together for the last time. ‘It’s been a very good ten years. Rest in peace’, he told the crowd.

As darkness descended on Dublin 4 and ‘Self Aid’ hit the home straight, the mood was escalated spectacularly and I’m not sure if the quality and breadth of that closing two hours will ever again be replicated on any national stage. ‘A man whose music has all the comforts of a long-time friend’, is how the songwriter and broadcaster, Shay Healy, introduced Rory Gallagher, who obliged us with four cracking cuts, including ‘Follow Me’ and ‘Shadow Play’. Elvis Costello and the Attractions were heralded into the ring by the broadcaster and publicist, B.P. Fallon, and tore into it from the off with a cover of ‘Leave My Kitten Alone’ leading a five song-set that also included ‘Uncomplicated’ and a snappy ‘I Hope You’re Happy Now’.

The Dublin-born actor, Gabriel Byrne, then introduced a magnificent short set by Van Morrison. Who, replete in suit, collar, tie and v-neck, and looking less like a musician and more like a fella on his way to a special pin presentation by the Pioneers, performed three numbers from an immense new album, ‘No Guru, No Method, No Teacher’. ‘Here Comes the Knight’, ‘A Town Called Paradise’ and ‘Thanks For The Information’ brought a balm and mellow to the outdoors: as has long been typical, Morrison paid little heed to his surroundings. And within the first four bars of his set, I’d already purged Chris de Burgh’s earlier performance from my mental hard-drive.

Although they’d played no overt part in the build-up to the event, U2 – and their considerable organisation – were all over ‘Self Aid’. Headlining the bill in their own back-yard, the group’s long-time manager, Paul McGuinness, sat on the Self Aid Trust, which was chaired by U2’s then accountant, Ossie Kilkenny. And it was the band’s live crew, led by production manager Steve Iredale and sound engineer, Joe O’Herlihy, who more or less ran the considerable technical operation at the arena. The original tapes in the RTÉ Archive library bear testament, in particular, to O’Herlihy’s gift and the live sound all day, as well as the live television production on-site, warrant particular mention here: I can’t recall a single, serious sound hitch across the entire day. And certainly nothing as obvious as the technical issues that ruined the start of Paul McCartney’s otherwise magnificent set at ‘Live Aid’.

My former colleague, the impregnable Jack Peoples, mixed the sound output for television, a production that was watched by almost 2.4 million people. That was more than had tuned into ‘Live Aid’ the previous year and represented over 90% of all homes watching television on the day, who each tuned in for an average of three hours.

Months previously, U2 fetched up surprisingly on a late-night RTÉ television youth programme called TV GaGa, where they debuted two new songs, ‘Womanfish’ and an early version of ‘A Trip Through Your Wires’, as well as a cover of ‘Knocking on Heaven’s Door’. During that performance, the band dragged a couple of young bucks from the bleachers and set them to work on guitars and percussion as part of the band.

A year before the release of ‘The Joshua Tree’ and knowing, I suspect, that they were sitting on absolute gold, U2 were in the same giddy humour at ‘Self Aid’. Their five-song set was a bit more considered and better upholstered, a mix of covers – ‘C’Mon Everybody’ and ‘Maggie’s Farm’, with popular staples, ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ and ‘Pride’. At one point, repeating the trick, Bono made into the front of the crowd and necked from a cider bottle with a bemused punter. He then went off on a couple of long, circular rants about work, life, choices, good fortune and semi-state agencies.

But during the band’s familiar encore – a lavish, lengthy version of ‘Bad’, he let fly with gusto. During a segue into Elton John’s ‘Candle in The Wind’, he took aim at In Dublin magazine and ‘Self Aid’’s various dissenters. ‘They crawled out of the woodwork’, he sang, ‘onto pages of cheap Dublin magazines’. It was a bizarre intercession and from my perch in Blackpool, and like most others watching in, I hadn’t a clue what he was on about.

After which Bono introduced Paul Doran onto stage and, with arguably the greatest ever group of Irish musicians gathered live on the one stage at the same time, the massed ranks closed the event with a rousing version – is there ever any other kind in such circumstances ? – of ‘Let’s Make It Work’. Featuring, for one night only, the best-known backing chorus ever heard on this island, consisting of Bono, Máire Brennan, Chris De Burgh and Bob Geldof.

The noise continued long after the three sound-stages in the RDS had been de-rigged. ‘Self Aid’ raised in excess of £500,000 on the day and 750 jobs were pledged, almost one in three of which were subsequently unsubstantiated or that didn’t come within the terms of reference as outlined by the National Manpower Service. A report in the following week’s Leitrim Observer claimed that ‘one job was pledged’ in the county, where a garage owner in Drumshambo, Michael McGowan, was looking for a diesel mechanic with at least five years experience. The ESB took the opportunity afforded by ‘Self Aid’ to create 20 jobs: at a period when the semi-state energy provider company was widely advertising the fact it was sitting on thousands of job applications, this begged the question: ‘Why?’. Tony Boland and Niall Mathews were accused of being well-intentioned but naïve, and a broader view was that ‘Self Aid’ did little to practically benefit the unemployed. Even if this, surely, was the responsibility of the state?

‘Self Aid’ also re-opened a familiar argument about the role of the national broadcaster and its relationship with the government, a question which has persisted as long as time itself. Uniquely in RTÉ’s case, the organisation is funded through a combination of public money and commercial revenues: it is expected to serve a broad public mandate and still be able to compete commercially. Since the launch of RTÉ Television in 1962, a tension has existed between the state classes, who often see public broadcasting as an instrument of public purpose, and the broadcaster, who see it as an instrument of public good. ‘Self Aid’ revived some of the key aspects of this conversation: was it really the place of a national broadcaster to raise funds for the unemployed, for instance? And, by wrapping this event in an entertainment context, was RTÉ not essentially de-basing the plight of those who were out of work and unwaged? And where, ultimately, is the line between the responsibilities of the state and the work of it’s national broadcaster?

Ultimately, many firms and small companies – what we might now refer to as ‘start-ups’ – sought financial aid from ‘Self Aid’. Hundreds of applications were assessed by various semi-state employment agencies on behalf of the Self Aid Trust, after which six different companies and community projects from all over Ireland received immediate help. Several hundred jobs were also directly created.

‘Self Aid’ was a spectacular under-taking and, in terms of its scale and ambition, and especially in respect of assembling the bill of performers it did, I’m not sure if RTÉ has come anywhere close to replicating it in the thirty-four years since. The entire concert was recorded and a double-album, ‘Live for Ireland’, later released: that record is very difficult to locate but contains a number of excellent live performances captured on the day of ‘Self Aid’, including ‘My Friend John’ by Sligo band, Those Nervous Animals, and ‘The Lark’ by Moving Hearts.

Harvey Goldsmith, who promoted the ‘Live Aid’ shows, was generous in his praise for the seamless manner in which ‘Self Aid’ had gone off, even if Tony Boland was a bit more circumspect. ‘I don’t think you could do it again’, he told The Sunday Independent. ‘I don’t think you could persuade all the acts to come together like that again. It’s a once in a lifetime thing’.

As an aside, it’s worth noting that a series of smaller, alternative live music events also took place across the country during the ‘Self Aid’ weekend. Including, memorably, a cluster of shows at The Underground on Dame Street in Dublin where, over three nights, The Stars of Heaven, The Gore hounds and A House all played sterling sets. The cost of entry to the unemployed was 50p.

‘Self Aid’ will be particularly remembered in Cork, and especially by the 900 punters who had gathered at The Opera House for a matinee performance of the musical, ‘Blood Brothers’. During In Tua Nua’s sparkling set at the RDS, an RTÉ transmitter, specifically erected on the roof of the Cork city centre theatre to carry live ‘Self Aid’ injects back to Dublin, was blown over, knocking a hole in the ceiling. After a residue of rain water swept into the backstage area, the building was evacuated and the performance cancelled. Accusations by some of the Blood Brothers’ production staff that the equipment wasn’t properly secured by RTÉ technicians were dismissed by the broadcaster: ‘It was a freak wind’, a spokesman told The Cork Examiner.

Six months after ‘Self Aid’, the ethical row was still bubbling away. A behind-the-scenes documentary about the event, produced by Billy McGrath, was aired on RTÉ television, in which, Eamonn McCann and Tony Boland once again put their respective positions onto the record. Apart entirely from re-cycling many of the ‘Self Aid’ live highlights, this fine documentary gave viewers an informed insight into the vagaries of event and television production. But far more importantly, it helped many of us to make some sort of sense of Bono’s performance at the R.D.S. months previously. And the row that had triggered him.

FÓGRA: There is an entire thesis to be written about ‘Self Aid’ and our piece here only really touches the surface. We chose not to include a mountain of material.

Its certainly worth noting though, that the formidable ghost of Philip Lynott book-ended the event. He died months previously after a short illness and, opening ‘Self Aid’, Brush Shiels, his one-time co-conspirator in Skid Row, dedicated his performance to him.

Although U2 formally headlined ‘Self Aid’, a Thin Lizzy line-up, featuring long-time band members Scott Gorham and Brian Downey, closed the concert with a short set, on which Gary Moore and Bob Geldof shared vocal duties.

Across Dublin, meanwhile, on the day of the ‘Self Aid’ concert, members of Philip Lynott’s family gathered again at the Church of the Assumption in Howth, where his eldest daughter, Sarah, made her First Holy Communion alongside children from the local school.

Philip Lynott’s funeral mass had taken place in the same church on January 13th, 1986.

Leaving Cert 1985 in mid- July?

Seems unusual

LikeLiked by 1 person

Its a typo, which we’ve corrected. June, obviously.

LikeLike

I think Harvey Goldsmith is British and not American.

LikeLike

He most certainly is. Thats entirely our copy mistake and we’re glad to correct it. Thanks for pointing it out. Colm

LikeLike

I watched the entire day from home as money was to tight to mention around that time , I would have seen a fair few of the acts in advance of the event at local gigs Limerick /Cork and really enjoyed the day s music and the productIon was excellent

I have both the double album and the double cassette . To be honest I viewed it as more a music event than a political one . I recall Paul Cleary being very opposed at the time and articulating his point of view which in fairness was pretty valid . It did no harm in raising awareness of the heavy unemployment situ we had in Irl but it was not going to solve it . I was thinking of the event last Friday night with the RTÉ Comedy relief and reflecting on that if you tried to do it nowadays with live Irish Music acts would you get the same viewership on RTÉ for a full day !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good post Colm but your comment on In Dublin is a bit unfair, in my opinion. In Dublin, even before Self Aid, was more than a listings magazine and was a great supporter of Dublin bands and Dublin music venues. It was also, under publisher John Doyle, a great vehicle of young Irish writers and was a strong political and social voice in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It’s anti-Self Aid stance was taken in good faith, even if not everyone would have agreed with it. Personally, I didn’t suport Self Aid but I respect those who did.

LikeLike

Thanks very much, Colin. That’s all fair enough, particularly in respect of emerging writers. But I still stick by my observation ! All the best. Colm.

LikeLike

Thanks Colm. Keep up the great work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You wrote: “But during the band’s familiar encore – a lavish, lengthy version of ‘Bad’, he let fly with gusto. During a segue into Elton John’s ‘Candle in The Wind’, he took aim at In Dublin magazine and ‘Self Aid’’s various dissenters. ‘They crawled out of the woodwork’, he sang, ‘onto pages of cheap Dublin magazines’. It was a bizarre intercession and from my perch in Blackpool, and like most others watching in, I hadn’t a clue what he was on about.”

You can find in the answer in Eamon Dunphy’s book about U2. At the end, there is an article reproduced from ‘In Dublin’ magazine. It was about Philo and this is the article Bono is referring to at Self-Aid. I guess you had to be there to get it… and, I suppose, living in Dublin and aware of the existence of the article and the slight controversy it caused. Read the article in Dunphy’s book and it will put Bono’s point into context.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for that, Eanna. The point I was making is that, if you weren’t from Dublin – and especially if you were from Cork, where a magazine called ‘In Dublin’ is and was perenially irrelevant, then you would have had no idea what Bono was on about. Which was the case. All the best. Colm

LikeLike

Of course, I could be wrong and you could be right. It’s just that Bono says “Love to you Phillip Lynott” and the end of the rant and maybe I put two and two together…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for that, Colm

LikeLike